- Home

- Eduardo Rabasa

A Zero-Sum Game

A Zero-Sum Game Read online

What Max noted was the inverse: despite its hyper-realistic pretensions, political narrative was acquiring an increasingly fictitious character. The point of departure and the end met to close a circle that no longer even bothered to take into account some of the most manifest features of any attempt to explain the social sphere. In years gone by, the graybeard who signaled the disenchantment of the world proposed setting out from “what is” as it presents itself, even as a point of departure for those who wanted to transform reality. In present times, the reverse process was followed: to set out from a list of indisputably good desires, and to assume that—with sufficient will on the part of those with power—one could reach a just Utopia where everyone would stay in the place corresponding to him.

“Villa Miserias is, of course, a microcosm, but Rabasa’s novel is anything but your simple society-in-miniature story. It’s an emphatically political novel, and willing to embrace theory, rather than just practice: there’s a discourse-framework here—some telling, rather than just showing—but Rabasa has a few tricks up his sleeve in this respect as well, and A Zero-Sum Game is decidedly (and for the most part successful as) an elaborately constructed fiction…A very impressive piece of work, in particular also in its creative approach to the concept of ‘political fiction,’ and in suggesting what fiction can still do.”

—MICHAEL ORTHOFER, The Complete Review

“When I heard that Deep Vellum were publishing this translation, I was ecstatic. Rabasa comes with much praise. Channeling both Orwell and Ballard, his dizzying and intricate dystopia exposes the demagoguery and inequality, the individualism and false democracy of the way we live now. A Zero-Sum Game is not only a brilliant novel—it’s the novel we need right now.”

—GARY PERRY, bookseller, Foyles Bookshop (London, England)

“How can a satirical farce be so dourly realistic? How can a precise and theoretical evisceration of neoliberal democracy also have such bloody guts and viscerally real characters? How did Eduardo Rabasa manage to make such a personal account of an individual’s crack-up into an anatomical sketch of political deadlock we find ourselves trapped in? And how did he make it so funny? Don’t answer these questions: just read the book.”

—AARON BADY, The New Inquiry

International Praise For A Zero-Sum Game

·Shortlisted for the PREMIO LAS AMÉRICAS, (for Debut Novel), given by the Festival de la Palabra from Puerto Rico to the best Spanish-language book of the year

·Selected among the 10 best books of the year by Nadal Suau, Periódico ABC (SPAIN)

·Selected among the 6 best books of the year by the literary blog, La medicina de Tongoy (SPAIN)

·Selected among the 10 best books of the year by Sergio González Rodríguez, Periódico Reforma (MÉXICO)

“A Zero-Sum Game is an outstanding political fantasy. Eduardo Rabasa has written a futuristic novel set in the present; its inventiveness is not based on new technologies but rather on new kinds of relationships. It’s a novel about the most complicated of extreme sports: cohabitation.”

—JUAN VILLORO, author of God is Round and The Guilty

“An amazing novel. On reading it, I felt myself to be immersed in a world that, as in certain works by Bolaño, transcends the characteristics typically associated with the Latin American novel. A Zero-Sum Game carries readers to regions of the imagination which subtly suggest the best of the Central European tradition. The sensation is as real as it is unsettling and, somehow, after a time, gives rise to an awareness of where we actually are. The prose rests firmly on a set of coordinates that can only be Mexican, revealing a totality of truths that reflect the complex texture of a country and a society immersed in a moment of violent convulsion. Few recent novels have managed to surprise me so greatly as A Zero-Sum Game.”

—EDUARDO LAGO, author of Call me Brooklyn

“The comparisons to Nineteen Eighty-Four are inevitable (…) However, A Zero-Sum Game is closer to A Brave New World than to the Orwellian dystopia.”

—VICTOR PARKAS, El País

“Meticulous, written with a harsh language, this is the portrait of a suffocating microcosm in which hierarchies are fixed by the illusion of a social progress that will never arrive. Rabasa dismantles with precision the mechanisms of a false democracy, in which no political alternation is possible (…) A mirror of some Latin American countries, this dense novel offers a pertinent reflection about the ways in which a regime can exercise violence today: less by outright repression and more through it’s capacity of imposing a deadly lethargy on people.”

—ARIANE SINGER, Le Monde

“This is an important novel. In terms of narrative, what the literary critics might call the central theme—power, our relationship with power, the power of power—is very deftly handled, and is combined with stories that interweave in perfect harmony. Rabasa’s decision to set the novel in an insignificant place, which works as a mirror to anywhere in the world, was a very wise one; more wise still is the satirical tone which reveals itself in his functional prose (that is, prose that functions well). Nowhere in recent times have I read a better portrait of how things are shaped – or how those things, over time, shape us.”

—JUAN BONILLA, author of Prohibido entrar sin pantalones, awarded the first PREMIO BIENAL DE NOVELA MARIO VARGAS LLOSA

“[Rabasa’s] first novel, A Zero-Sum Game, collects outbursts of passionate love, of the conflicting relationship between a father and a son, and, above all, of a critique to democracy in the shape of political satire…Rabasa gives an unexpected turn to the genre of novels of social criticism, a literary tradition from which the author hopes to obtain the formula that allows him to think and understand the present…A demolishing piece of work, perfectly suited for Rabasa, an eternal restless soul, and one who invites to share in the pleasure of literature from his double role as a publisher and writer.”

—LEONARDO TARIFEÑO, Revista Vice

“Rabasa’s satirical vocation is cristallized in a cumulative effect that at times recalls the transversal cut with which Georges Perec sketched the life of the tenants of a building in La Vie mode d’employ, or the eagle-eye with which Damián Tabarovsky followed the comings and goings of a leaf that glides over a street of Buenos Aires in his novel-essay Una belleza vulgar.”

—GUILLERMO NÚÑEZ, Frente

Deep Vellum Publishing

3000 Commerce St., Dallas, Texas 75226

deepvellum.org · @deepvellum

Deep Vellum Publishing is a 501C3

nonprofit literary arts organization founded in 2013.

© Eduardo Rabasa 2014

First published in Spanish as La suma de los ceros in 2014 by Surplus Ediciones, Mexico City, Mexico

English translation copyright © 2016 by Christina MacSweeney

First edition, 2016

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-941920-39-8 (ebook)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CONTROL NUMBER: 2016945227

The publisher is grateful for permission to reproduce the following extracts:

“A Wolf at the Door,” by Thomas Edward Yorke, Philip James Selway, Edward John O’Brien, Jonathan Richard Guy Greenwood and Colin Charles Greenwood.

Warner/Chappell Music LTD. All rights reserved.

The Unquiet Grave, by Cyril Connolly © 1944.

Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Anatomy of Restlessness, by Bruce Chatwin © 1996.

Used by permission. All rights reserved.

White Noise, by Don DeLillo © 1985.

Used by permission. All rights reserved.

The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, by B. Traven © 1927.

Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Cover design & typesettin

g by Anna Zylicz · annazylicz.com

Text set in Bembo, a typeface modeled on typefaces cut by Francesco Griffo for Aldo Manuzio’s printing of De Aetna in 1495 in Venice.

Distributed by Consortium Book Sales & Distribution.

Table of Contents

Part One

Part Two

Epilogue

Author & Translator Bios

PART ONE

Walking like giant cranes and

With my x-ray eyes I strip you naked

In a tight little world and are you on the list?

Stepford wives who are we to complain?

Investments and deals investments and deals

Cold wives and mistresses

Cold wives and Sunday papers

City boys in first class

Don’t know they’re born little

Someone else is gonna come and clean it up

Born and raised for the job

Someone always does

I wish you’d get up get over get up get over

Turn your tape off.

“A Wolf at the Door”

Radiohead

I

1

All I ever wanted was to be just another invisible coward, Max Michels silently grumbled as a drop of blood dribbled down his freshly shaved throat. Almost unconsciously, he’d put off until the very last moment the decision that, once taken, seemed as surprising as it was irrevocable. He was about to break the cardinal rule of Villa Miserias: to stand as a candidate in the elections for the president of the residents’ association without the consent of Selon Perdumes.

With the force of a rusty spring unexpectedly uncoiling, the memory of an era before Perdumes’ arrival materialized in his mind. Max clearly recalled the principal feature of the day the modernization began: jubilation at the sight of the dust. There was no lack of people who gladly inhaled the first particles of the future. Poor devils, Max now thought. The dust had never cleared: Villa Miserias was a perpetual work in progress.

At that time the residential estate had functioned like clockwork; it still did, although the model was now completely different. Every two years there were elections for the presidency of the estate’s board. For eleven days, the residents were bombarded with election leaflets. The most distinguished ladies received chocolates and flowers; those of lower standing had to make do with bags of rice and dried beans. In essence, all the candidates were competing to convince the voters they were the one who would make absolutely no alterations to the established order. There was even a physical prototype for those in charge of running the estate that included, in equal measure, the fat, the short, the dark, and bald: it was a bearing, a gaze, a malleable voice. There was no friction between the election manifestos and the everyday state of affairs.

The foundations of Villa Miserias were conceived on the same basis as Selon Perdumes’ fundamental doctrine: Quietism in Motion. Its forty-nine buildings were constructed using an engineering technique designed to allow shaking while avoiding collapse. The smear of city to which it belonged was prone to lethal earthquakes, but the flexible structure of the buildings had prevented catastrophe on more than one occasion.

In the time before the reforms all the apartments had been identical; now they were symmetrically unequal. Each building had ten in total, distributed in inverse proportion to the corresponding floor. In general, the demography was also predictable: in the tiny apartments on the lowest floor, multiple generations of humans and animals lived together. In contrast, the penthouse apartments were usually inhabited by young executives with or without wives and children. In exchange for their privileged position, they had to endure the swaying motion of the building, some of which was caused by the passage of buses on the broad road surrounding the estate. One such resident, who had a panoramic view of the earthquake that reduced the neighboring estate to rubble, defined the spectacle as a waltz danced by flexible concrete colossi.

Perdumes delighted in the improbable equilibrium of successful social engineering. His conversion into Villa Miserias’ foremost resident was a gradual process. He’d arrived on the estate as a businessman of mysterious origins and activities. Each person who spoke to him received an explanation as vague as it was different to the others. To give a clearer idea of his character, one only has to say that—so far—it’s reasonable to imagine they were all true.

He moved into apartment 4B in Building 10, having offered its owner, the widow Inocencia Roca, a year’s rent in advance in exchange for a substantial discount. The inhabitants of Villa Miserias—accustomed to the traditional barter system—weren’t prepared for the way Selon Perdumes flashed the greenbacks. Señora Roca was unaware that she would soon be signing over the apartment to him.

Sightings of him were rare: he kept them to the bare minimum. In order to introduce himself to his neighbors, he invited them individually for coffee. He was charming in the most chameleonic sense of the term. His eyes were the shade of gray that can be taken as either blue or green. He was able to guess the most deeply hidden fears of each of his guests and had an amazing talent for giving solidity to fantasies, then offering the finance needed to make them real. The calculated non-payment of a proportion of his creditors was, for him, a great blessing since he practiced a different sort of usury. In exchange for the possibility of being ruined, he sought to acquire loyalties and secrets. Like an expert dentist who extracts a molar without his anaesthetized patient being aware, his magnetism attracted confessions that enabled him to understand people via their weaknesses.

The young couple in 4A became the subjects of one of his first laboratory experiments. After an informal chat, Perdumes noted the tensions inherent in their different origins. The young man had followed in his father’s footsteps to become a public accountant; she’d studied literature in a state university thanks to the family Popsicle business. He’d been stagnating in an accountancy firm for two years; she worked as the assistant of an impressively learned academic.

Perdumes explained to them that when it came to making an impression, appearances were everything. Enveloping them in the gleam of his alabaster smile, he told the young man that he should change his old car and buy a new watch. Fine, but that was impossible, they could scarcely cover the mortgage…Eyes downcast, she confessed that her mother helped pay for her painting classes. Marvelous! Don’t worry, replied Perdumes’ smile. I’ll loan you as much as you need and you can pay me back in installments. He was a master of the art of silence. Without moving from his seat, his presence seemed to lose density while the couple made their decision. Of course, they would repay him as soon as possible. It’s just a springboard…Great! No problem. Would you like more coffee?

He also happened to know that some women in the building were interested in forming a reading group. Why didn’t she organize it? This time the silence was more ephemeral. The girl’s eyes lit up with an enthusiasm her husband hadn’t seen for a long time. Phenomenal! Don’t say another word. Would you excuse me a moment?

Within a few weeks everything was different. The young man was driving a modest new car; he checked the time regularly on his elegant casual watch. Every week, she listened to the heavily made-up ladies who spoke about anything but the books they had briefly skimmed through. His employers noted the change and began shake his hand when they met. They once asked him to join them for lunch in the small restaurant near the office. She was able to pay for her painting classes for as long as Perdumes’ clandestine subsidy to the ladies of the reading group lasted. Every weekend, the couple turned up with radiant smiles to present their repayments.

To explain his theory of secrets, Perdumes used the analogy of the reversible red velvet bags used by magicians. The first step is to show the audience that the bag is empty inside and out. Nothing hidden there. However, the trick consists in inserting a hand in the right place. The commonest secrets are as innocent as white rabbits. Then come the shameful secrets, greasy stains that can be removed with a little effort

. As he honed his extraction technique, Perdumes became interested in the secrets that could only be invoked by a black magic ritual. They were barbs that gave pain by their mere existence: the smallest movement lacerated the soul in which they were embedded.

On one occasion, Perdumes noticed that the logo on a young neighbor’s sneakers had an A too many and was missing an E. When little Jorge felt the gleam of Perdumes’ smile scrutinizing his footwear, he knew the secret was out. He subjected his mother to a weeklong tantrum that only abated with the arrival of a box containing a pair of authentic sneakers. There was also the elderly lady in 4B who used to fill the bottles of holy water she sprinkled on her grandchildren on Sundays from the tap. Or the aged bureaucrat in 2C who boasted of his mistreatment of the Villa Miserias cleaning staff: “Better harness the donkey than carry the load yourself.”

Perdumes’ prying was sustained by an age-old activity: gossip. Having gained a little of a person’s confidence, he was able to access what they knew, suspected or had invented about others. It was an unashamed downward spiral: other people’s dirty laundry covered your own to the point where you created a hodgepodge of stinking gibberish, crying out in a muffled voice: “Deep down, we’re all disgusting, so there’s nothing to worry about.” It made no difference that the secret was an invention. What mattered was the perception of that dark thing and its tangled strata. Everyone had something to hide; other people found out about it. The gossip came alive, spreading like a virus that by nature mutated on infecting each new host. Attempts to deny the gossip gave rise to other, more poisonous rumors. Making use of the most innocent gestures, Perdumes would communicate that he knew the very thing no other person should know.

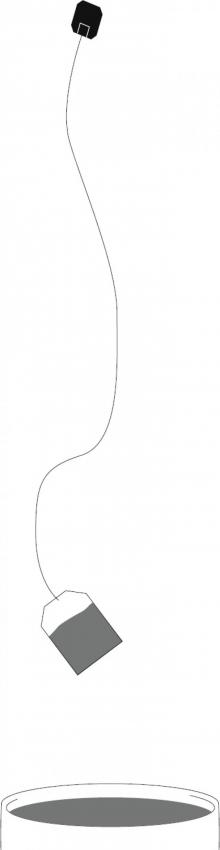

Very soon Perdumes had fabricated a network of correspondences woven from founded and unfounded rumors. Whether out of gratitude, respect or fear, the residents in his building adored him: all collective decisions passed through his hands. His indefatigable mind processed the situation until it hit on the two pillars of Quietism in Motion: the theories of the sword and the tea bag.

A Zero-Sum Game

A Zero-Sum Game